In the fall semester, students in the IAA program participated in a two-week communication training where we created a presentation on a topic of our choosing. As a lifelong basketball fan, I chose to share the differences in 3-point attempts over time in the NBA. While researching statistics and trends for this presentation, I was not met with any surprises. NBA players were attempting more 3s, and NBA teams were crafting rosters based on this trend. Shortly after communication training ended, the NBA playoffs began. After watching the first few rounds of the playoffs, I noticed two players who gave their teams mismatch advantages in the playoffs – a pair of sharpshooting centers. I thought back to the presentation I had created just a few weeks prior and realized an implication of the 3-point explosion I had missed: the death of the traditional NBA center.

From 1970-2010, the formula for a franchise-caliber center was one with few variables. Teams wanted a post man with incredible size, rebounding abilities, and an extensive repertoire of post moves. In 2008, a center would earn himself a cozy spot on the pine right beside the assistant coach for launching an open 3 instead of driving to the rim. Today, that same player would find himself benched for not letting an uncontested 3 fly.

In the past 12 years, the formula for a franchise-caliber big man has changed so much that nearly all cornerstone attributes have been nixed in favor of one new, more valuable one: a 3-point jump shot. While centers may no longer be the most popular or dominant position in the league, the sharpshooting center is a far better asset on the court.

It turns out practicing something makes one better at it. In some regards, this seemingly intuitive concept was foreign to the National Basketball Association for over 40 years. Centers that practice their 3-point attempts improve their ability to knock them down in games. If a team’s center can shoot from 3, defenses are forced to respect a new threat. When defenders must move out of the lane and go contest a center from behind the arc, the offense can create more space on the court, more lanes to the basket, and tougher rotations for the defense.

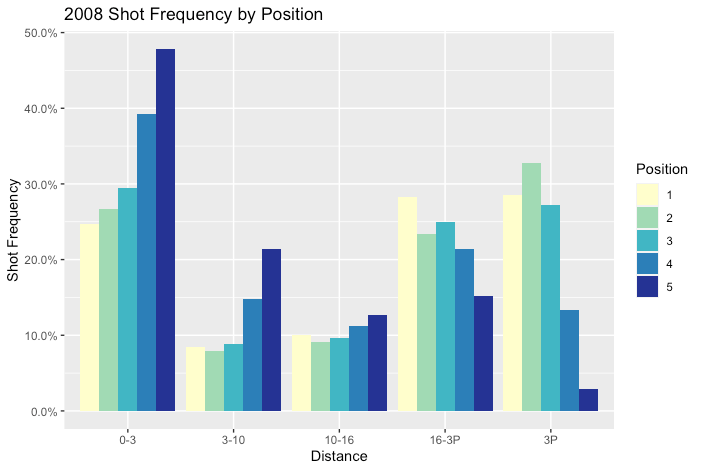

The concept of taking more 3s is not unique to the center position. In fact, centers today still take the fewest number of 3s on the team. However, the addition of the 3-point shot has optimized and transformed the center position in more ways than any other on the court. Figure 1* below shows the difference in the percentage of shots attempted from various distances on the court. The figure illustrates differences in these percentages between the 2008 season and the most recent 2020 season.

Figure 1. Percentage of Shots Taken by Position and Distance

There are two main takeaways from these charts. First, centers are shooting approximately 6 times as many 3s compared to 2008. Second, the number of shots taken from 0-3 feet and 3-10 feet does not seem to have changed. When investigating how the center position’s shooting has evolved, it becomes obvious that the midrange jumper has seen the most change.

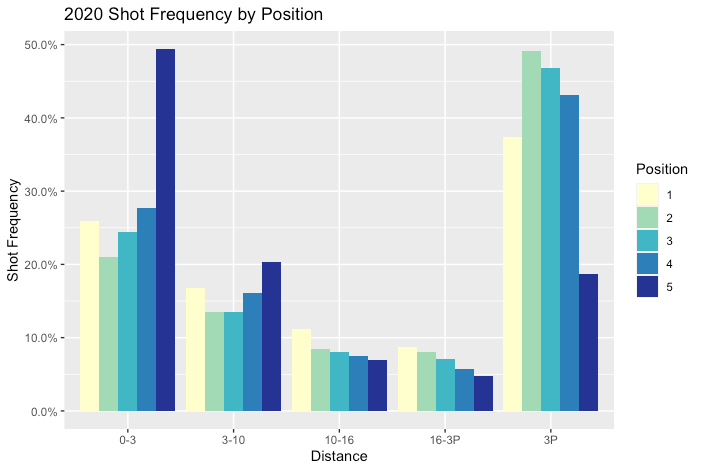

In 2008, the death of the mid-range jump shot for centers did not make sense. Big men were simply not accurate enough from 3 for teams to encourage this type of shooting. To better illustrate the shooting differences from each year, Figure 2 shows the accuracy for players in each position from each spot on the court.

Figure 2. Field Goal Percentage by Position and Distance

The improvement across most positions is slight; however, the differences between the centers and the power forwards are stark. From 2008 to 2020, the accuracy of centers from 3 increased 300%. While this increase suggests centers have become better shooters, expected values indicate 3-pointers have also become better shots.

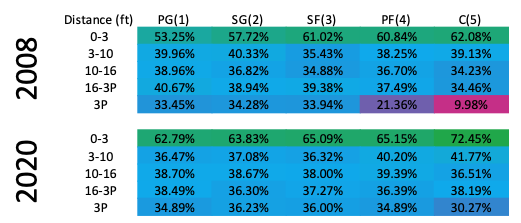

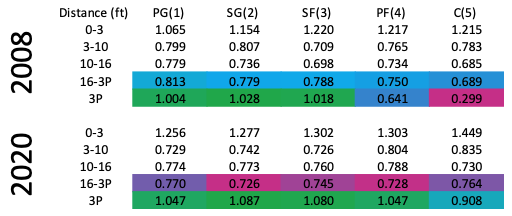

Figure 3 shows the expected value for each position from every spot on the court. Expected values illustrate the projected number of points a player will earn from a shot based on their accuracy from that distance and the amount of points that shot is worth. For this figure, only long-range 2-pointers and 3-pointers are highlighted.

Figure 3. Expected Value by Position and Distance

Figure 3 supports a double-edged point. The table validates the old-school aversion to 3-point shooting while vindicating the new-school obsession with it. In 2008, a center could expect more than double the expected value from midrange than he could from behind the arc. For a center in 2008, a long-range 2-pointer was a better shot than a heave from 3-point distance. In 2020, this is no longer the case. Centers in 2020 can expect almost a 20% increase in their expected value by taking a few steps back and making that midrange jump shot a triple.

It should come as no surprise that throughout both 2008 and 2020, centers take the largest majority of their shots from where their expected value is highest. This is inherently the correct way to allocate shooting since maximizing the number of points scored is something every player, team, and coach wants. While centers shoot better from 3 today than they did in 2008, a closer look at Figure 3 offers a slightly more shocking revelation: centers shoot better from everywhere. While it is impossible to narrow down that increase in accuracy to one variable, better 3-point shooting emerges as a willing challenger to the task. The improved spacing created by a sharpshooting big man offers him easier looks at the basket, more pick-and-roll dunks, and even more space to dish out assists.

Coaches and organizations are privy to analytics. Some of the most successful NBA teams today pride themselves on their attention to data and the quality of their analytics. The analytics are clear on this one: better 3-point shooting from a center translates to better offense for their team. For a guy who grew up at the height of the Shaquille O’Neal, Dwight Howard, and Kevin Garnett era, seeing a big man pull up from 3 will always feel unnatural. But as a lover of statistics and analytics, watching Nikola Jokic cut defenses to pieces with his elite 3-point shooting and “Magic-esque” passing will always leave me shaking my head with a smile.

Columnist: Rob Elmore

*All statistics have been taken from Basketball Reference on players that participated in at least 50 games that season. All subsequent analyses have been performed by me.

Data Column | Institute for Advanced Analytics

The Collaborative Blog for Students in the Master of Science in Analytics